Reblogged from TheTorah.com – A Historical and Contextual Approach

[1] See M. Zipor, Tradition and Transmission: Studies in Ancient Biblical Translation and Interpretation [Heb.] (Tel Aviv, 2001), pp. 79-165. The sources were collected by C. D. Ginsburg, Introduction to the Massoretico-Critical Edition of the Hebrew Bible (second edition: New York, 1966), 347-363.

[2] Or perhaps just before classical rabbinic times, in the period of the so-called Men of the Great Assembly (אנשי הכנסת הגדולה).

[3] Beshalah 16.

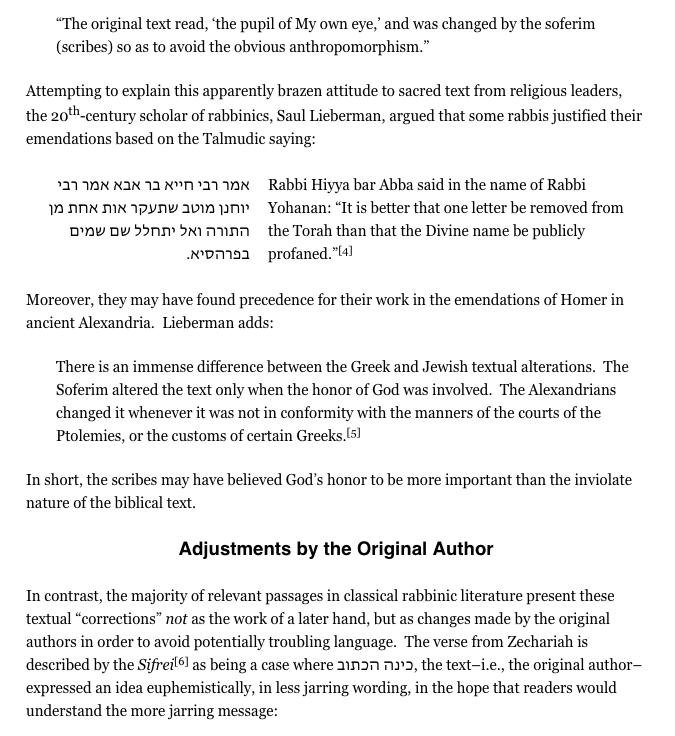

[4] Hellenism in Jewish Palestine (New York, 1962), p. 35, quoting b. Yevamot 79a.

[5] Lieberman, p. 37. See also Michael Fishbane’s chapter, “Pious Revisions and Theological Addenda,” in his Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel (Oxford, 1985), pp. 66-75.

[6] ספרי במדבר פרשת בהעלותך פיסקא פד.

[7] The standard interpretation sees YHWH here as the name of the deity; Rashbam, however, sees it as the name of one of the three angels. See my Rabbi Samuel ben Meir’s Commentary on Genesis, pp. 58-59 and my Peirush Rashbam al ha-Torah, pp. 20-21. The need for a scribal correction here could be argued according to either understanding of YHWH.

[8] This example is also discussed in Ben Katz’s TABS essay on Parashat Vayera, “God’s Appearance to Abraham: Vision or Visit.” Katz works with the assumption that the scribes did in fact alter the verse from what it said originally.

[9] Bereshit Rabbah 49, p. 505 in the Theodor-Albeck edition.

[10] Ginsburg (above note 1), p. 353.

[11] Livorono, 1475. This book was one of the first Hebrew books ever printed. Scholars generally believe that it preserves a very reliable version of Rashi’s commentary for the most part.

[12] Rashi and Rashbam both think YHWH’s words in vss. 20-21 are directed to Abraham.

[13] In two other places in his Bible commentary Rashi seems to assume that a “scribal correction” means that a later hand changed the text (commentary to Job 32:3 and Mal 1:13), but the language there is not as clear. See the discussion in Yeshayahu Maori, “Tiqqun Soferim and Kinah Hakkatuv in the Commentary of Rashi to the Bible” [Heb.], in Netiot leDavid: Jubilee Volume for David Weiss Halivni, ed. Y. Elman et al, (Jerusalem, 2005), pp. 104-105.

[14] Berliner was one of the leading religious scholars of the “Science of Judaism” approach in the nineteenth century. Among other activities, he was one of the editors of the prestigious Magazin für die Wissenschaft des Judenthums.

[15] See also Menahem Kasher’s Torah Sheleimah on the verse in Genesis. Kasher follows Berliner’s opinion that Rashi could not have written those words.

[16] Pp. xiv-xv.

[17] Rabbi Solomon ibn Adret (the Rashba, 1235-1310), Rabbi Eliyyahu Mizrahi (1435-1526), the most famous of Rashi’s super-commentaries, the Minhat Shai commentary of Rabbi Yedidyah Norzi (1560-1626) and Me’or Einayim of Azariah de Rossi (1513-1578). The first three of these, however, never suggest a different reading of Rashi’s commentary. They only argue for the understanding of the phrase “scribal correction” in classical rabbinic sources as meaning self-censorship done by the original authors.

[18] De Rossi seems to be an unusual candidate for the role of defender of Rashi’s orthodoxy. De Rossi was one of the first Jewish history writers to use many aspects of scientific method in his writings, and he himself was accused of unacceptable heterodoxy by some of the leading rabbis of his time.

[19] Me’or einayim, chapter 19 (Vilna, 1865), p. 232.

[20] Commentary to Gen 18:22.

[21] Little is known about Bokrat who was active in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and was among the Jews expelled from Spain. His Sefer ha-zikkaron was published in a good edition by Moshe Filip (Petah Tiqva, 1985). For a brief analysis of Bokrat’s approach, see the introductory essay in my Rashbam’s Commentary on Deuteronomy: An Annotated Translation (Providence, 2003), pp. 11-15.

[22] See Elazar Touitou, “Concerning the Presumed Original Version of Rashi’s Commentary on the Pentateuch” [Heb.], Tarbiz 56 (1987), 211-242, esp. p. 231, note 30; Yeshayahu Maori, “Tiqqun Soferim and Kinah Hakkatuv in the Commentary of Rashi to the Bible” [Heb.], inNetiot leDavid: Jubilee Volume for David Weiss Halivni, ed. Y. Elman et al, (Jerusalem, 2005), 99-109; and Aharon Mondschein, “Rashi, Rashbam and ibn Ezra on the Phenomenon of Tiqqun Soferim,” [Heb] in Studies in Bible and Exegesis 8 (2008), 409-450. As Mondschein and Maori both point out, despite the fact that Touitou found the problematic four words in the preponderance of Rashi manuscripts, Touitou did not consider the words part of Rashi’s original commentary. Mondschein (especially p. 412, note 13) and Maori (especially p. 103, note 19), argue convincingly against Touitou.

[23] The Ha-keter edition (Ramat Gan, 1992-2013). Maori (ibid.) quotes the unpublished rationale of Professor Menahem Cohen, the editor of Ha-keter, for his decision to print these four words in the Ha-keter edition as part of the original text of Rashi’s commentary. See also H. Dimitrovski’s notes in his edition of Rashba’s responsa, p. 178: ונר’ שזהו הנוסח האמיתי בלשון רש”י.

[24] Such attempts to rewrite history and “clean up” the work of an earlier rabbi are not so rare. See e.g. my Rashbam’s Commentary on Leviticus and Numbers: An Annotated Translation, pp. 260-261, where I argue that Rashbam’s commentary to Num 22:1 was altered for religious ideological reasons. And see more generally Marc Shapiro’s recent book,Changing the Immutable: How Orthodox Judaism Rewrites its History, concerning the phenomenon in contemporary times.

[25] Maimonides, commentary on the Mishnah, Sanhedrin 10.

It goes without saying that this vindicates the Quran’s position on the Torah.

@ Paul

Hahahahahahahaha. Oh, you are a scholar and a gentlemen good sir. I guess there’s no need to prove anything since they all appear to concede it

https://quranandbibleblog.wordpress.com/2018/04/21/missing-books-in-the-bible/

Soooo… I just realized this is now EXTREMELY awkward on the missionary side:

Jews: We changed our text.

Missionaries: No you didn’t!

Reblogged this on The Quran and Bible Blog and commented:

Even Jews admit that the Tanakh has been altered! When will the missionaries accept reality?!

I don’t think you are capable of accepting reality

Says the doorknob who thinks it’s an intelligent person. 🤭

There was no need to “correct” the text.

All three “men” walked a short distance towards Sodom and then Abraham and one of the men stopped. The other two men kept on walking towards Sodom.

It is understandable that some Jews would find this text offensive and feel the urge to correct it.

From a christian point of view it fits in well with the New Testament revelation of God.

@ Erasmus

Well other than being anthropomorphism the point is not what they corrected but the fact that they corrected period.

I don’t see any evidence of a correction.

if jesus did not rise from the dead , how much do crosstians worry about offending the yhwh in the old testament?

thinking about this question makes you realize how different the gods of christianity are.